This is Part Two of the Alexanderplatz Series. If you missed part one, you can read it here.

Let’s continue our trip around the majestic, if often misunderstood and underappreciated, Alexanderplatz, the beating heart of the city for the last two hundred years.

The former Centrum Warenhaus

We’ll pick up this week by looking at the Galeria Department store sitting next to the train station. Although the building was substantially reconstructed and its façade utterly modernized after German reunification, what you’re looking at was once the joy of the former East German consumer, such as they were.

Its story begins in 1970 when today’s building first saw the light of day as the Centrum Warenhaus, one of the largest department stores in the DDR. At the time, it was a symbol of socialist pride, showcasing the supposed success of East Germany’s planned economy.

Designed with a bold, modernist aesthetic, the Centrum Warenhaus was originally clad in a sort of wavy metal exterior, which sadly hasn’t be preserved. Its massive, rectangular facade of glass and steel exuded a sense of modernity and industrial power, which was precisely the image of the DDR itself that the comrades were trying to project. Inside, it was meant to offer East German citizens a glimpse of consumer abundance, with multiple floors filled with everything from household goods to clothing. In reality, though, shortages were common, and many shelves were bare—a stark contrast to the West’s glittering consumer paradise just a short distance away.

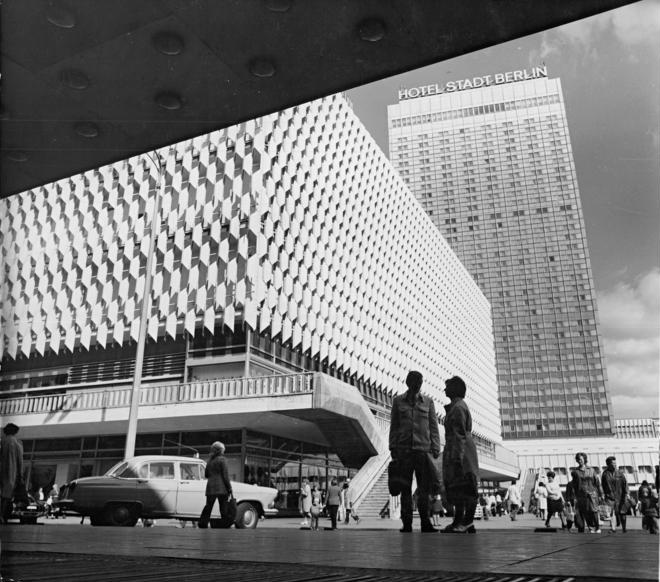

Below: Showcases of Planned Economi in the DDR – Centrum Warenhaus and Hotel Stadt Berlin

For East Berliners, the department store was more than a place to shop. It was a hub of social life, a gathering place, and a symbol of their city’s status as the nation’s capital. However, the state-run economy just couldn’t keep up with a rapidly changing global consumer culture, and like much of East Germany, the Centrum Warenhaus was a facade of prosperity, hiding the economic struggles underneath.

Then came 1989, and the fall of the Berlin Wall. The building, like East Germany itself, was soon to be transformed. With reunification, Western investors quickly moved in, and the store was privatized, undergoing major renovations. In the early 2000s, the old Centrum was reborn as the Galeria Kaufhof, a glitzy, modern shopping mall catering to a united Berlin’s rapidly changing consumer tastes. You’re free to make up your own mind about the relative merits of the modern redesign into yet another soulless 21st century mall, but the building, at least to me, stands for the hopes and dreams of the communists, dashed to pieces against the capitalist urges that humanity can’t seem to rid itself of. Where else but Berlin can a simple mall spark a political discussion? Ultimately, that’s the charm of the place, I’d argue.

The former Tietz Department Store site

The place where the Galeria stands is itself history haunted. Today’s building was constructed in 1970 more or less right on the spot once occupied by the legendary Imperial era department store called Tietz. Opened in 1904, it was part of a booming retail empire, owned by Jewish entrepreneur Leonhard Tietz. The store quickly became a symbol of modern consumerism in Berlin, offering luxury goods, fine fashions, and the latest trends, all under one roof. With its grand façade, one of the longest in Europe, and elegant displays, Tietz revolutionized the shopping experience for Berliners in the decades either side of the First World War, becoming a byword for a grand day out shopping.

But like much of Berlin’s golden era, the Tietz legacy was cut short by the rise of the Nazis. In the early 1930s, the Tietz family was forced out of their business as part of the regime’s anti-Semitic policies, and the store was «Aryanized» and renamed Hertie. By the end of World War II, the building was severely damaged by bombing, and the ruins were eventually replaced by the DDR’s Centrum and today’s Galeria. It’s a storied bit of real estate indeed.

The InterHotel Stadt Berlin/Park Inn

Just next to the Galeria, you can see the towering edifice of the former InterHotel Stadt Berlin, which after reunification was rebranded as Park Inn by Radisson, and like its neighbor was reclad to «update» its appearance.

The former InterHotel Stadt Berlin was a grand statement of East Germany’s literally towering ambitions. Standing tall on Alexanderplatz, the hotel played a significant role in the DDR’s effort to showcase its version of modernity and progress to the world as well as to its own citizens.

Construction and Symbolism

Completed in 1970, the InterHotel Stadt Berlin was the tallest building in the city, soaring 125 meters high. The hotel, with its stark modernist design, embodied the socialist aesthetic of functionality over decorative excess. It represented not only a place to stay but a statement of the state’s ability to build impressive, forward-looking structures, emphasizing utility and equality, with clean lines, geometric shapes, and practical forms. The facade was stark, minimal, and lacked the ornamental flourishes common in western designs, emphasizing the utilitarian ideals of socialism. Remember, when you look at communist architecture, you’re looking for not only the pure function of the building but also its deeper message.

International Showpiece

The InterHotel Stadt Berlin formed part of the InterHotel chain and thus hosted citizens and representatives of the state, the Communist party and visitors from other socialist nations. The Stadt Berlin Hotel thus had a distinct political role. But it was used to host international visitors, from foreign dignitaries to journalists and businessmen, and was one of the places where the East German regime attempted to control the narrative about what the communist state’s achievements were.

Foreign guests were meant to be impressed and to take that message of success home and spread the word. The hotel was equipped with a variety of amenities that were rare in East Germany at the time, such as international restaurants, bars, and conference facilities. It was a place designed to impress, offering the best that East Germany could afford its guests.

However, this attempt at impressing the outside world often just ended up underlining the contrasts between the DDR’s ideals and its reality. For many ordinary East Germans, the luxury of the Hotel Stadt Berlin was out of reach, a stark contrast to the austere, everyday conditions experienced by most of the population. While foreigners and party members might be treated to lavish meals, the local citizens were often dealing with food shortages and limited consumer goods.

Surveillance and the Stasi – And Hotel Stadt Berlin

As with many high-profile public spaces in East Germany, the Hotel Stadt Berlin was under constant surveillance. The Stasi, East Germany’s secret police, had a significant presence in and around the hotel. Rooms were bugged, phone calls monitored, and hotel staff were often informants.

Guests could never be sure if they were being watched or listened to, which could create, in the minds of those inclined to drama, an atmosphere of tension and paranoia. This was, in many ways, a microcosm of life in East Germany during the communist era — an impressive facade hiding a darker reality of surveillance, control, and repression. Today that atmosphere is all gone, replaced by the trappings and the vibe found in any modern hotel. The views however remain impressive, and the bar on the top floor is a good place for a drink, and to reflect on the ever-changing nature of this most interesting of squares.

Next week, we’ll finish up our brief exploration of the area, after which you’ll have a good grasp of what Alexanderplatz really offers you unparalleled insights into Berlin’s changing nature over the decades.