Berlin is a city of strong contrasts and profound ironies. If you want to get a taste of that, head down the great Unter den Linden to Bebelplatz, right in the historic center of the city.

Bebelplatz – Where the 1933 Book Burning took Place

The Night That Literature Was Turned to Ash: The 1933 Book Burning at Bebelplatz

It was here on May 10, 1933, in one of Europe’s great squares, that an act of political vandalism took place whose images still make our blood run cold today. Thousands of people gathered in the middle of today’s Bebelplatz, known then as Kaiser-Franz-Joseph-Platz , a public square flanked by prestigious institutions like the Humboldt University and the Opera House. They came, however, not to celebrate art and literature but to annihilate it.

Organized by the German Student Union, the event marked a grim milestone in Hitler’s quest to build a new Germany by means of controlling thought itself. Students, professors, and Nazi officials united in a belief that certain ideas were dangerous. Over 25,000 books—works by Jewish, liberal, socialist, and pacifist authors—were consigned to a bonfire that had been kindled in the middle of the square.

Joseph Goebbels: «Burning Books – Cleansing the German Spirit»

The night’s events were choreographed with chilling precision. Students marched in torch-lit processions, carrying banners inscribed with slogans condemning «un-German» thought. Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s Propaganda Minister, gave a fiery speech declaring, «The era of extreme Jewish intellectualism is now at an end.» He proclaimed the burning a symbolic act of cleansing the German spirit, casting the destruction of «improper» literature as a moral imperative. The people gathered there that afternoon and evening saw themselves as warriors of virtue, certainly not mere vandals. They were, in their minds, doctors purging a sick patient of disease.

The books burned that night included works by Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Helen Keller, Erich Maria Remarque, and Thomas Mann, among others. Many of these authors represented ideas that the Nazis deemed antithetical to their vision, including concepts like racial equality, pacifism and individualism. The students involved claimed they were defending German culture from what they saw as these corrupting influences.

Heirich Heine: «Where they burn Books, They will also burn People»

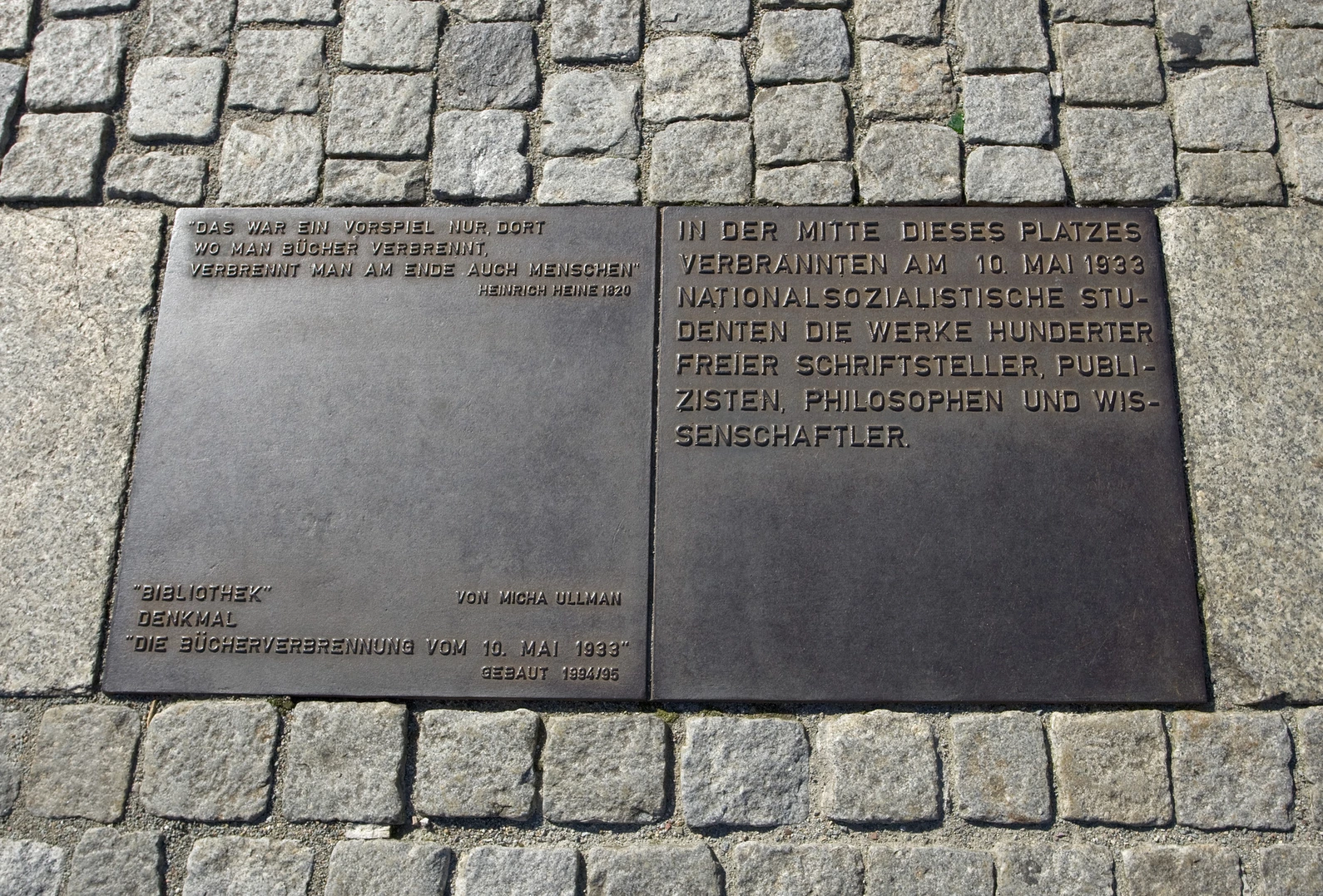

For those who witnessed the flames as bystanders rather than believers, the implications were terrifying. Heinrich Heine, a German poet whose works were among those burned, had written a prophetic line nearly a century earlier, about the Spanish Inquisition but chillingly relevant to 1933: «Where they burn books, they will also burn people.»

Today, a haunting memorial stands beneath the square: a glass pane in the ground revealing an empty, underground library with enough shelf space for the 25,000 books destroyed that night. Inscribed on metal plaques fixed to the ground next to the memorial are Heine’s chilling words, which never fail to send a shiver down the spine.

It started with enlightenment…

What makes this memorial to the book burnings so heartbreakingly poignant is that it all took place in one of Berlin’s towering architectural monuments to enlightenment virtues, the heart of all that aspired to the best in the old Prussian capital. Long before the Nazis, the area that became Bebelplatz had been laid out under the direction of King Frederick II, arguably Berlin’s greatest monarch. A warrior and a poet, a leader who spoke fluent French, debated Voltaire and played the flute like a virtuoso, Frederick was in many ways far ahead of his time. The area that later came to be called the Frederick Forum, which includes Bebelplatz, became an expression of Frederick’s guiding principles.

If you want to get an idea of what the place looked like before modernity got its hooks into it, then remember that the old city of Berlin was located to the north and the east of the river Spree, centered on the place where the enormous TV tower is today. The city walls and fortifications protecting the palace and the old city itself ran very close to the future site of the square. Imagine then a semi-rural location, with new housing just being put up, and this enormous complex dedicated to virtue lying just outside the walls. In other words, it made an impressive statement.

Let’s try to understand how this place looked, to get a feel for it at a deeper level. Stand next to the Unter den Linden on the edge of Bebelplatz, where you can see the equestrian statue of Frederick the Great on your left, and the Opera House on your right. The enormous Humboldt University should be across the street from your position.

Originally, you’d be looking at three squares. Only today’s Bebelplatz remains identifiable as a proper platz. Originally, there was a small square surrounding the statue of Frederick, and another larger one in front of the Opera House. Bebelplatz marked the third, and largest, square. Unter den Linden ran through the squares and eventually became a major thoroughfare, destroying the harmonious symmetry of the area by the first half of the 20th century. By the mid-1930s, the place looked as it does now.

Take a few steps now into Bebelplatz itself, until the TV tower disappears from view, blocked by the Opera House. This is one of those insider tips; you’re now in one of the vanishingly few places in the heart of Berlin where you can imagine that the Second World War and the DDR had never happened, since your view here is substantially what it was back in the days of Kaiser Wilhelm II at the turn of the 20th century. Stop to take in the feeling, and then look around. As you do, what you’re looking at is essentially King Friedrich’s vision for what makes for an enlightened state. Let’s start with the elegant Opera House, on the east side of the square.

The Opera House – Staatsoper Unter den Linden

The Opera House saw its first performance in 1742, and was the first of the new monumental buildings erected in the area. The king seems to have had several overt propaganda statements in mind with this structure. Opera was all the rage, but opera houses in this era tended to have been built within, or directly adjacent to, palaces. By building a free-standing opera house, the message went out that this grand spectacle was to be made available to a wider audience. It took awhile to happen, however. The first years of its existence attendance was still restricted to the military officer class and their fellow aristocrats. But still, a vital start towards making high-level performance art accessible was begun.

The Operahouse – Not only Opera – Also a Political Meaning

In addition to this gesture, Frederick went a step further. The king was involved in one of his many wars at the time, and his Kingdom of Prussia was regarded by other Europeans as little more than a semi-barbaric armed camp. To combat this reputation, Frederick had the Opera House built to establish in the minds of his enemies that there were tangling not only with a great military power, but also a growing cultural powerhouse as well. Not for the first time in Berlin’s history was architecture meant to convey a concrete political meaning.

St Hedwig’s Church – Symbol of Berlin´s Diversity

Next, move your eyes to the right, towards an odd building that wasn’t originally meant to be here at all when the first plans were drawn up. It looks like a cross between the Pantheon in Rome and an overturned tea cup. What you’re looking at is St Hedwig’s Catholic church.

The king himself had a direct hand in designing this, the second building to be built on the platz, and the choice of the Pantheon in Rome as a model was not accidental. The Pantheon had been designed in antiquity as a temple for «all the gods» and Frederick’s new church was making a bold statement of religious tolerance.

In the mid-1700s, Frederick conquered an area of central/eastern Europe known as Silesia. This area was rich in resources and was strategically located vis-à-vis the Polish kingdom and the Hapsburg empire. Yet Silesia was Catholic. St Hedwig, the patron saint of Silesia, was chosen to be the patron of the new church in Berlin, in an effort to welcome and integrate the Catholics of Silesia into Protestant Berlin. Religious tolerance it may have been, but it was also a shrewd political gesture, echoing the similar welcoming of the French Huguenots in the previous century.

Bebel Platz – Not only Bookburning – Also Symbol of Tolerance and High Culture

There’s a great deal more to say about this area of Berlin, and we’ll tackle the next part of the Bebelplatz in the next story. But already you can get a sense of the spirit of this place; a platz that reflects the greatest of Berlin’s spirit – tolerance and making high culture accessible to all – hosting one of the city’s great acts of barbarism, the book burning of 1933. Berlin’s contrasts and ironies are never-ending. If ever there was a city built for reflection, it’s this one.

Address

Bebelplatz 1,

10117 Berlin

Public Transport

Bebelplatz is well-connected by public transport:

Bus: Lines 100, 147, and 300 stop near Bebelplatz.

U-Bahn: Lines U2, U5, and U6 stop at U Museumsinsel (a short walk away).

S-Bahn: Lines S2, S3, S5, and S7 stop at Friedrichstraße (a short walk away).