Echoes of Extremes

Berlin is a city of contrasts, a place of constant transformation, where monuments built by one regime are reinterpreted and repurposed by the next. But in the heart of the city stands a building that takes Berlin’s signature irony to a whole new level. This is the Detlev Rohwedder Haus, once the Nazi Air Ministry, built in 1936 and located at the intersection of Wilhelmstrasse and Leipziger Strasse. For anyone visiting Berlin, this place is a must-see—a powerful testament to the complex layers of history that still shape the city today.

A Profound and importand Place in German Military History

It’s a haunted piece of ground. It might be going too far to claim it as the epicenter of 20th century European history, but as a symbolic «center of gravity» for the last century’s Age of Extremes, you could do far worse. The territory that today’s building sits on was before the 30s the site of the Prussian, and then Imperial German, Ministry of War. It was partly from this square block that defense policy and the waging of the First World War was partly decided and planned.

When the present building was finished in the summer of 1936, it was the largest office building in Europe, and one of the largest in the world, and housed the Air Ministry, containing as well Luftwaffe, the German Airforce’s central offices.

Miraculously escaping major damage in the war, (the front line was essentially at the Air Ministry when Berlin surrendered in early May 1945), the building was swept from being an emblem of the far right to be becoming one of the administration buildings of the Red Army. From Nazi military, to Communist military, in the snap of a pair of fingers.

Rohwedder House becomes The House of Ministries

In 1949, the new communist state, the DDR was formally announced from the main room of the former Air Ministry and become the new House of Ministries, housing primarily the heads and offices of the ministries concerned with industry and economic expansion. It’s at this point that we get to the element of the building that is often missed or brushed over in public tours, but which gives us a meaningful insight into the struggles and the ironies of Berlin’s mid-century history.

The people running the new DDR were of course firmly away aware of their new ministry’s headquarters role under the Nazi regime. The party leader Walter Ulbricht and the DDR’s Prime Minster Otto Grotewohl, commissioned the artist Max Lingner to create a mural along the north wall of the ministry building, to give it a sort of «socialist air.»

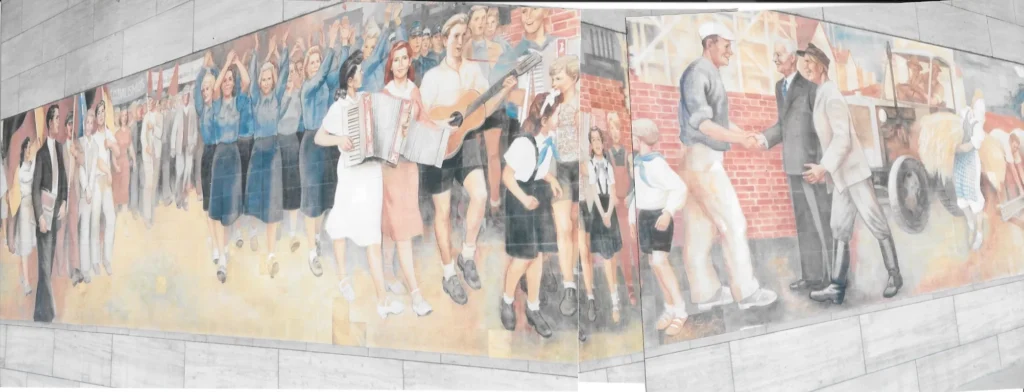

You can still see the result today, almost hiding behind the columns forming part of the façade of the building at the intersection of Leipziger and Wilhelm Strasse. Except what you see wasn’t what Lingner initially designed. The first version was a mural showing families rebuilding after the war for a peaceful future. For the government, this wasn’t political enough, and the design went through no less than five reworkings, until neither Grotewohl nor Lingner liked the final product.

Socialist Realism

What they finally agreed to, however reluctantly, was today’s mural. It’s made of Meissen ceramic tiles, spans a full 60 feet and shows us industrial workers, planners and farmers working to build the «radiant future» together. All the characters are smiling, all are working together, and none feel particularly authentic.

We now have a chance to really get to grips with the deeper story this site is telling us. The style of art is known as Socialist Realism and it originated in the Soviet Union of the 1920s. Here we have a German twist in terms of the what the scene consists of, but the mural remains the only genuine Stalin-era item of public art still on display in Berlin. But what, exactly, was Socialist Realism?

As you study the mural, you’ll notice that while it’s not abstract, it’s also far from being grittily realistic. It doesn’t portray the exhaustion, dirt, or internal conflicts that shape real life. Socialist Realism, the genre this mural exemplifies, actually forbids such realism. Depicting the gritty realities of life in public art was considered counter-revolutionary and subversive. By highlighting present struggles, art reveals the lingering mess left by the old order and the difficulties of bringing about change—images that do nothing to uplift or unify. Here, truth isn’t found in today’s imperfections but in the bright, optimistic future the Party envisions. It’s not about reflecting life as it is but life as it should be, according to the Party’s grand design. Although the mural shows the building of the new world, it has to do so in a pure way, devoid of suffering or mistakes.

With only some exaggeration, you might think of this as an almost religious-inspired view of the world. The ultimate reality, the «truth,» is not to be found now, but in the next life, the upcoming life, or here in the radiant future of a soon-to-be-realized Communist world. That noble idea is what we must show people, the party believed, rather than depicting the lesser and misleading «truth» of what life was really like today with all its hardships and shortages.

When you look at the Lingner mural and absorb this view of the world, you’ll have taken a huge step towards understanding the nature of the communist state, both in the DDR and in the rest of the old Warsaw Pact nations of the Cold War era. The goal was to depict the essence of truth, not the realities of the «actually existing socialism» of today, to use their words.

A Nazi-era Meeting

The dark power of this place runs yet deeper. Just above the alcove with the mural, in the conference room whose windows are visible from where you’re standing, another meeting took place in 1939, led by Hermann Goering. This gathering, held in the aftermath of the November 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom, focused on drafting stricter anti-Jewish laws, as the National Socialist regime pursued its own vision of a utopian—or rather, dystopian—world. Here we find two extremist regimes, a decade and half apart, each driven to reshape society entirely in their own image, regardless of the human cost, and regardless of any objective notion of what the truth actually was.

«The Party is always right,» as the DDR anthem had it. Truth is whatever the Party – Nazi or Communist – decides it is. Few places reflect that way of thinking more powerfully than this one.

Revolt

In 1953, the small square in front of the new mural saw the gathering of many hundreds, even thousands, of protesters. These workers had gathered here to protest the raising of a new quota on the building of the new Stalin Allee and their protests resulted in a near-successful overthrowing of the regime. Only Soviet tanks and extreme violence restored order. In 2000, a photograph of that uprising, showing exhausted angry people, frowning and upset, was placed in the ground. The revolting workers contrast sharply with the Socialist Realist workers depicted in the mural and offers endless food for thought.

There’s much more to say about this building, but I believe I’ve shared enough to spark your curiosity. Standing in the square before the mural, let your thoughts dwell on the questions this place asks. Who holds the power to shape the future? Who decides what reality is, and where truth resides? Is a «radiant future» truly worth pursuing if its creation and survival depend on fear and force? Like all of Berlin’s profoundest sites, this place whispers its questions. It’s up to you to listen—and craft your response.