There’s little doubt that many people travel to Berlin to track down what remains from the city’s turbulent 20th century history. If you’re reading this blog, there’s an excellent chance you’re one of them!

If you happen to be a first-time visitor, you might imagine that the best place to begin your exploration of the old city is in the city center. A quick glance at a map suggests that the mighty Alexanderplatz would suit, being the central transportation hub that it is. Seems logical, right?

Right! Or rather, right, but you’ll be hard pressed to find anything that predates the 1960s in Berlin’s historic center. Those coming to search for traces of the Kaiser’s capital, or the Babylon Berlin of the Roaring 20s, or Hitler’s Hauptstadt will likely leave disappointed and even confused.

The reason for this apparent historical desert is the very history you’ve come in search of. War, extremist political programs, and the utter turbulence of the previous 130 years have done barely conceivable violence to the old town. Yet, there are a couple of buildings that do fit the bill for those in search of Weimar and Third Reich Berlin, and those buildings are almost chameleon-like in appearance. They seem so modern, or at least so late-Communist, that you can be forgiven for giving them a passing glance before moving on. That, however, would be a mistake.

Masterpeces of 20th Century Modernism

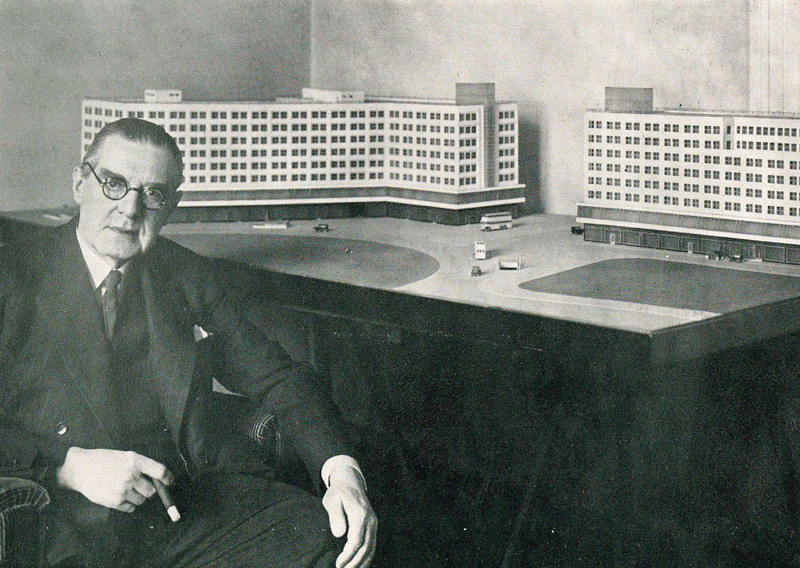

The two buildings I’m referring to are masterpieces of 20th century Modernism. Berolinahaus and Alexanderhaus face the elevated S-Bahn line and were completed in 1932 by the famed architect Peter Behrens.

By the 1920s, Alexanderplatz had become the beating heart of post-Great-War Berlin and it was getting too small for the increasing demands placed on it. So, in the late 1920s, as the storm clouds of political violence and incipient economic ruin gathered on the horizon, a competition was held to redesign the great square, and bring it fully up-to-date and fit to serve as the crossroads of the world city that the old Imperial capital had already become.

Behrens was awarded the contract and the first two buildings he designed become the buildings you see today at the side of the square facing the Alexanderplatz train station. Behrens designed them in a style known as New Objectivity. Much can be said about this, but we’ll limit ourselves to noting that the movement sought to bring back sobriety and functionality to structures. Buildings ought to avoid the (to them) silliness and extravagance of the Art Nouveau movement, with its nature motifs and grand arches and curves. Buildings of the future should be sober, and reflect the qualities of not only the building materials but also of the activities that went on inside. Hence the reason why most modern visitors look past these structures; they just look too… ordinary to us.

But in their day, they made a statement. You’ll notice, when you visit, that a road separates Behren’s two buildings. On the other side of the tracks, this street was once one of Old Berlin’s main roads. The idea was that a traveler going from what was once the crowded old town would pass under the tracks and through these two Modernist masterpieces, which formed a sort of gateway into the new, expanded Alexanderplatz.

The buildings ended up surviving the war with some damage, but nothing that couldn’t be repaired. The Soviet command ended up using Berolinahaus as one of its headquarter buildings for a few years, before being turned over to the newly consecrated state of East Germany.

After renovation, the building housed central Berlin’s administration and on the ground floor you could find the Communist state’s first proper fast-food hall, which consisted for the most part of vending machines and high tables to stand and eat at.

When the Wall fell, the building was restored and despite some cosmetic differences, looks from the outside substantially like it did in the early 1930s, making it a rare bird indeed for this historic but surprisingly modern looking square.

So, if you’re in Berlin and find yourself starting your exploration at Alexanderplatz, be sure to look for Berolinahaus and its sister Alexanderhaus. These are two buildings that saw the last of Weimar, and were buildings that Hitler and the people of the Third Reich knew very well, given their relative fame as flagship structures in the city’s newly rebuilt main square. They certainly formed a key part of the mental mindscape of the DDR era’s Communist state and are known to every Berliner today.

So the Berolinahaus might not look like much to us today, but let your gaze linger on its practical facades and let your imagination take over, as you reflect on how such a seemingly banal-looking building can have witnessed so much over the decades. It’s great training for understanding the mood of the city as a whole, as often in Berlin the banal is often gripping. Stories are everywhere here.