Berlin’s soul has been forged by revolution – from the creative ferment of artists and writers to the clash of ideologies in its streets. While the fall of the Wall in 1989 remains its most celebrated uprising, another pivotal moment in the city’s history unfolded during two sweltering days in June 1953, when East Berliners in the new Communist state, the DDR, dared to challenge Soviet power for the first time. The fact that they gained lasting concessions from the regime makes it all the more remarkable.

Every story needs a beginning, and ours starts with an ending. When Joseph Stalin died in his Moscow dacha in March 1953, the news reverberated across the Soviet empire like a thunderclap. The man who had helped defeat Hitler, but then imprisoned half of Europe behind an Iron Curtain, was gone. In the uneasy quiet that followed, people throughout Eastern Europe began to imagine something that had seemed impossible just months before – the chance, however dim, for change. They began, quietly at first, to breathe more freely and to imagine that socialism in East Germany could proceed with a more human face.

The Uprising

But events went otherwise. Instead of a more progressive approach, the East German leadership decided to go the other way. The government, trying to maintain its ambitious economic goals, demanded that workers increase their output by 10% without any corresponding rise in wages. For East German laborers already struggling with food shortages and harsh living conditions, this was the final straw. The government had also recently increased public transportation fares and raised prices on basic consumer goods, making an already difficult situation nearly impossible for many workers.

On June 16, around 300 construction workers from Stalinallee (now Karl-Marx-Allee) marched to the House of Ministries, carrying signs demanding the quota increase be reversed. The House of Ministries, an imposing building that had once housed Hermann Göring’s Air Ministry during the Nazi period, was a seat of governmental authority in East Berlin. The workers gathered in front of its massive facade, their numbers growing as office workers leaned out of windows to watch the unprecedented scene unfold.

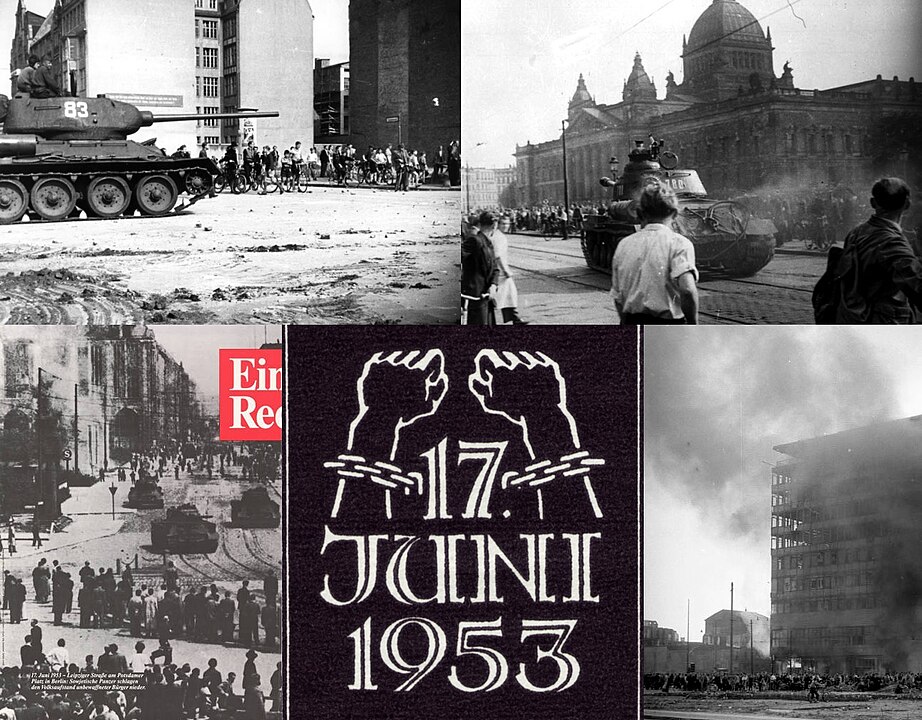

By the next morning, the demonstration had swelled to include over 40,000 people in East Berlin alone, with similar protests erupting in nearly 700 locations across East Germany. The uprising spread rapidly to major industrial centers including Leipzig, Dresden, and Magdeburg. The government was thrown into a panic, despite announcing by the end of the day to reduce the quotas to what they had been before. The people paused in their protest for the evening, but perhaps feeling their power, marched out again the next day, with greater demands.

The morning of June 17 saw East Berlin transform into a city of protest, as columns of workers converged on the city center. Starting from gathering points like Strausberger Platz, the crowds grew rapidly – police and party officials tried and failed to stop them, while demonstrators used loudspeaker cars and bicycles to coordinate their movements. By 9 AM, some 25,000 people had gathered at the House of Ministries, with tens of thousands more heading toward Party Headquarters and others towards Potsdamer Platz. Their demands were now calls for change, with protesters carrying banners demanding things like «butter, not arms» and calling for free elections. As they marched, they tore down party posters and shouted their anger.

The Soviet response came swiftly and brutally. Between 10 and 11 AM, after protesters had overwhelmed the 500 Volkspolizei and Stasi guards at the House of Ministries, Soviet tanks and military vehicles rolled into the city center. By noon, they had shut down public transport and largely sealed off East Berlin from the West. The Soviets declared martial law at 1 PM and began clearing the streets, leading to violent confrontations that continued into the night. The aftermath was harsh: up to 10,000 people were arrested in the following days, and dozens were executed, including, according to some sources, several Soviet soldiers who had refused to follow orders. With East Germany’s leadership seeking safety at the Soviet headquarters in Karlshorst, control of the city had effectively passed to the Soviet military command.

Protests continued until the 24th of June, albeit on a lesser scale. Today, the best estimates suggest a total death toll of around 125 people killed in the clashes directly. The results of the uprising were interesting, to say the least. Many Communist party members tore up their membership cards in disgust and quit the party, unable to support violence against the very people the state was designed to protect and promote. The Stasi, the secret police, get a fresh lease on life, ultimately growing into the most pervasive security organ in world history, certainly in modern history, far surpassing both the Nazi era Gestapo and Stalin’s NKVD/KGB. The leadership ultimately, after the uprising in Budapest in 1956 drove them to further spasms of fear, decamped to a secure compound outside Berlin itself.

Yet the workers also achieved something by their sacrifices and efforts. The quota was reduced. Never again would the DDR raise quotas unilaterally across the board. Their power had peaked, then, in some sense in 1953, and a certain caution and consideration for the population entered into their decision-making processes hereafter. Ultimately, the regime decided to focus more on producing better consumer items and making life a bit better for the people. This effort still fell far behind what people in the west enjoyed, but at least the effort was there.

The western powers had supported the uprising with radio broadcasts into the east, understanding the potency of this soft power. The revolt also handed them a propaganda coup, stressing as it did the failure of communism to work by anything other than brute force, and failing to produce decent results even with force. They renamed the road through the Tiergarten (in the western sector) which led to the Brandenburg Gate (in East Berlin) to the «Street of June 17th» as a constant provocation to the east. If that weren’t enough, June 17th became a national holiday in West Germany, replaced by Unification Day in October after the reunification. The Street of June 17th still remains, although few people today understand what it means any more.

Remnants Today

For today’s visitors to Berlin, several locations offer powerful connections to the 1953 uprising:

Karl-Marx-Allee (formerly Stalinallee) remains largely unchanged since 1953. The grand Soviet-style buildings where the protest began still stand, offering visitors a glimpse into the architectural ambitions of East Germany. The wide boulevard, stretching from Alexanderplatz to Frankfurter Tor, was specifically designed to loosely mimic the main roads in Moscow, albeit with a German flair. Ironically, it became a line of advance for tanks sent by Moscow to crush German resistance.

Strausberger Platz, one of the main squares along Karl-Marx-Allee, was a crucial gathering point for protesters. Today, it serves as an excellent example of preserved East German urban planning and architecture, with its distinctive twin towers flanking the entrance to the square.

The former House of Ministries, now the Federal Ministry of Finance on Leipziger Straße, still stands. In the small plaza on Leipziger Straße itself, just in front of the building, you can find a photo installation and some information stands in place, which commemorate the events of the uprising in one of its key spots.

The SED (the German Communist party) headquarters of the era also still stand, and witnessed the revolt. It’s now called the Soho House, and it’s located on Tor Straße, with a façade almost unchanged since 1953. An information sign stands outside the building, giving you the essential background of this fascinating building.

Today’s Legacy

Berlin, as I’ve often said, offers endless talking points and lessons for us today. What began with construction workers on Stalinallee would eventually, if indirectly, contribute to the fall of the Berlin Wall 36 years later. To me, this suggests strongly that no system of control, however powerful it may seem, is truly permanent when faced with the collective will of ordinary people demanding change. This is surely a vital lesson for us today. In that sense, those fateful, far-off June days still resonate, their lessons echoing down to us all these decades later. Berlin never fails to fascinate.